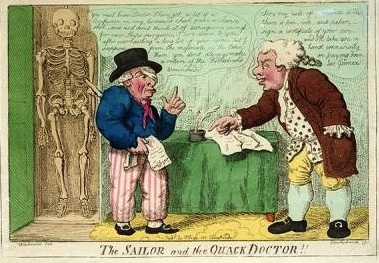

In the eighteenth century, legislation to protect the public from quack doctors and other medical charlatans was still in its infancy.

Here’s an example from a Norwich newspaper of 1767 where the magistrates made use of such legislation as was available to them to send a quack scurrying on his way out of their jurisdiction. The fact that he appears to have been a foreigner might also help to explain their prompt and vigorous action.

To detect Impostures of any Kind is deserving the Thanks of the Public and is in no Instance of greater Utility than to expose and suppress that Species of it, which, under pretence of extraordinary Skill in Medicine, commit merciless Depredations on the credulous and necessitous. A Foreigner, who calls himself Dr. Fortunatus Benvenuti has for several Months past strolled about this Kingdom Sumptuously dressed, in a handsome Chariot with two Servants in Livery; after having been permitted with Impunity to continue many Weeks at Leicester, Birmingham, York, Liverpool and other Places, he lately infested this City, to the additional Distress of many diseased and indigent Persons. On Monday he was summoned before the Mayor and two other Justices of the Peace … he was called upon for his Authority for Travelling in England, he said he had the King’s Letter, which appeared to be a Foot Licence from the Commissioners of Hawkers and Pedlars[1] upon the whole Examination he appears to be destitute of Knowledge, Medicines and Instruments to perform the wonderful Cures he pretended to effect, except an Apparatus for Couching, and tolerable acquaintance with the Anatomical Structure of the Eye … the Magistrates finding himself, a Woman who passes for his wife, and the Servants were Vagabonds according to the Vagrancy Act[2], acquainted them that unless they quitted the City that Afternoon they should be committed to the House of Correction for six Months: accordingly, to the Relief of the Poor (whom he pretended to cure Gratis, altho’ each paid a Shilling to the Servant before they were admitted to an Audience with the Doctor) and much to the Credit of the Magistrates who exerted themselves in their Favour, they decamped immediately.

We’re used to travelling today whenever and wherever we wish. It’s therefore important to recall these extinct legal provisions. Any ordinary person—not one of the gentry or someone of the middling sort following an established trade or profession—who was found on the roads in the eighteenth century was in danger of being hauled before the magistrate to explain themselves. If they could not produce the appropriate permission or licence, they would be threatened with being deemed a vagabond and punished accordingly.

- A pedlar typically travelled the countryside on foot, hawking goods to people in small towns and villages. Legitimate traders of this kind had to purchase an annual licence and carry it as proof of their legal status. The disparity between the humble pedlar’s licence the man produced and the skilled profession he claimed proved to the magistrates that he was a fake. ↩

- Vagrancy legislation had been in place since the 16th century, building into a range of statute laws that treated vagrancy and vagabondage as a social evil deserving serious punishment. Under the 1714 and 1744 Vagrancy Acts, those whom a magistrate deemed to be vagabonds could receive a public whipping, followed by six months in the House of Correction. ↩