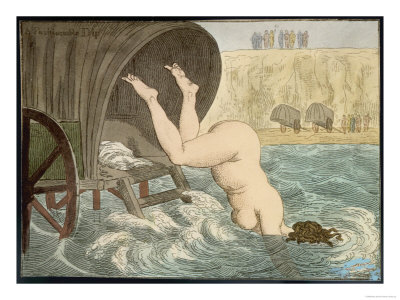

Early sea-Bathing.

Note the “gentlemen” ranged along the cliff-top to watch! Many brought telescopes.

A little while ago, I wrote a post about sea bathing. It attracted so much interest I thought more research would be useful, going beyond the basics into the reasoning behind the fashion and how it changed during the 18th century.

At the start of the period, going to the seaside was a serious business, to be undertaken only on medical advice and for the purposes of restoring health. It definitely wasn’t any kind of recreation or holiday activity. Not so long before, the sea had been universally feared and the shore, with its piles of decaying flotsam, regarded as places of decay. A few medical men first began to consider the sea and seaside in a radically different way in the 1730s and 40s. Gradually, they became interested in the curative properties of sea-water, and a number of treatises appeared on the subject. Traditionalists opposed the idea, stressing that full immersion in water with either dangerous or encouraged lascivious thoughts, incest, and general moral turpitude – mostly because of the nudity involved.

What changed people’s outlook so greatly that, by the 1750s, they were flocking to bathing resorts in unprecedented numbers?

The Moral and Physical Decay of the Gentry

In England in the eighteenth century many of the upper classes were obsessed with the idea that urban living and the modes of life it encouraged caused a general ‘decay’ of strength and vitality. They ‘better class’ of people appeared prone to frailness, listlessness and lack of vigour, especially in comparison to the robustness of the lower and labouring classes. They felt themselves cut off from nature and liable to bouts of melancholy, or ‘spleen’,. This could only be cured by a change in style of living to include exercise in rural sports, periods spent in a variety of landscape, and therapeutic bathing. The ills of civilisation were all around you, moral, intellectual and physical.

Thoughts about the beneficial aspects of sea water were also linked to enthusiasm for periods spent at the many spas promoted by entrepreneurial medical men. This was the great age of the inland spas with their warm medicinal mineral springs. Those who went on the Grand Tour might also notice the popular sea-bathing traditions in much of coastal Catholic Europe. There the sea was credited with prophylactic powers against all kinds of illnesses. Naturally, opponents of the practice in England dismissed the very idea as a corrupt, continental practice, liable to introduce the kind of low morals everyone knew the French and Italians favoured!

This physical weakness and ennui amongst the upper classes was believed to herald a general decline in morality. The nobility hardly set a good example to the lower classes. The newspapers and pamphlets were full of salacious tales of adultery, bigamy, rape and licentiousness in the landed classes – to say nothing of the gambling away of fortunes, drinking to excess and widespread contempt for standards of proper behaviour[1]. In time, it was feared, the people would lose all respect for the gentry and thus dismiss the idea that they should always be the natural leaders of the country.

What could be done to reverse this tide?

Time to Toughen Up!

In the 1750s, many doctors began to recommend cold baths as well as hot springs. Hot springs were ‘enervating’ where cold water was invigorating. This idea remained potent for many years. Dr William Buchan wrote in “Domestic Medicine” (1819) that:

“The cold bath recommends itself in a variety of cases; and is peculiarly beneficial to the inhabitants of populous cities; who indulge in idleness, and lead sedentary lives. In persons of this description the action of the fluids is always too weak, which induces a languid circulation, a crude indigested mass of humours, and obstructions in the capillary vessels and glandular system. Cold water, from its gravity as well as its tonic power, is well calculated either to obviate or remove these symptoms. It accelerates the motion of the blood, promotes the different secretions, and gives permanent vigour to the solids. But all these important purposes will be more essentially answered by the application of salt water.”

“The Sea washes away all the Evils of Mankind”

What better cold bath could you find than the sea? There was no thought of pleasure connected to sea bathing in its early days. Bathing, and drinking sea water, were strictly medicinal. All aspects of the practice were strictly prescribed by your doctor. ‘Messing about in the briny’ only came many decades later, naturally restricted to the warmer months.

The north-east coast of England, around Whitby, was being sought out for bathing by the 1720s. The first proper sea-bathing resort was Scarborough, where bathing machines were in use from 1735 onwards. After that, others joined in throughout the country. Now the south and east coasts were generally favoured as being more convenient for London. However, the big break for their operations came in 1752, when Dr Richard Russell published “A Dissertation on the Use of Sea-Water in the Diseases of the Glands. Particularly the Scurvy, Jaundice, King’s Evil, Leprosy, and the Glandular Consumption”.

He was not the first physician to praise the benefits of seawater. He was, however, one of the best at publicity, and his catchy slogan, “The Sea washes away all the Evils of Mankind” became known far and wide. He assiduously publicised near-miraculous cures from drinking seawater and bathing in the ocean. How much effect sea-bathing really had is hard to say, but daily bathing, fresh air and exercise would certainly not do anyone much harm — especially overweight, hard-drinking, soft-living gentry and rich merchants.

Sea-bathing was often prescribed for ‘delicate constitutions’ in order to toughen them up. Eliza de Feuillide, Jane Austen’s cousin, was urged to take her delicate son Hastings to Margate for sea-bathing in January, on the basis that “…one month’s bathing at this time of year was more efficacious than six at any other.” Later, Eliza told her cousin, Philadelphia Walter, “The sea has strengthened [Hastings] wonderfully and I think has likewise been of great service to myself. I still continue bathing notwithstanding the severity of the weather and frost and snow, which I think somewhat courageous.”

Nothing Pleases Everyone

Not everyone enjoyed either sea-bathing or the seaside. Charles Lamb wrote:

“We have been dull at Worthing one summer, duller at Brighton another, dullest at Eastbourne a third, and are at this moment doing dreary penance at – Hastings! – and all because we were happy many years ago for a brief week at Margate.”

He went on, “I cannot stand all day on the naked beach, watching the capricious hues of the sea, shifting like the colours of a dying mullet.”

John Byng, Viscount Torrington, wrote in his diary of his dislike of crowded watering-places:

“They are, for a healthy person, a miserable way of killing time, and spending money; with new acquaintance for whom we care not a jot, and toss’d about in bad company, and bad conversation; divested of quiet and comforts.”

A resident of Great Yarmouth wrote to the local paper in 1772 complaining about the regular influx of visitors there:

“… for my part, when I see the carriages with their numerous appendages whirling into the town, I look upon them with as much dread as I should so many swarms of locusts: equal devourers of the fruits of the earth – comforting myself, however, that the climate will not long agree with their summer constitutions.”

Nevertheless, sea bathing continued its rise in fashion and popularity, especially after King George III visiting Weymouth in 1789, following his recovery from his first bout of madness. Fanny Burney recorded it thus in her diary:

“Nor is this all. Think but of the surprise of His Majesty when, the first time of his bathing, he had no sooner popped his royal head under water than a band of music, concealed in a neighbouring machine, struck up “God save great George our King”.”

Jane Austen, in her unfinished novel ‘Sanditon’ wrote, perhaps somewhat satirically:

“The Sea air and Sea Bathing together were nearly infallible, one or the other of them being a match for every Disorder…”

And her heroine, Anne Elliot, in ‘Persuasion’ had “the bloom and freshness of youth restored” by her visit to the seaside.

Of course, soon all the commercial trappings of luxury and pleasure found at the more sophisticated spas were readily transferred to this new setting. That’s how the Victorian resort began to establish itself as mostly a location for summer frolics. Still, the romantics valued the seaside as a sublime aspect of nature, very suitable to artistic compositions. Gradually, the medical aspect of bathing was overwhelmed by less strenuous notions of promenading, enjoying the views and the bracing sea air and playing on the sands.

The archetypal British seaside resort had arrived.

- Pretty much the same as celebrities today! Every generation indulges in much the same moral panics and assumes nothing like them has happened before. ↩

Thank you, that was very interesting facts. Life was much easier in our past. If only my condition need to go in the ocean. I wish it was that easy to be healed!

LikeLike

This certainly shows how human thinking about health can change over time. I can’t imagine a world where no one swam in the ocean, having grown up on Atlantic shores. I missed your previous post but assume people went in naked? When did the idea of bathing suits arrive?

LikeLike

Naked at first, yes. Bathing attire for women (like long, flannel nighties with weighted hems) were becoming established by the 1770s and men followed by 1800.

LikeLike

Thanks. History is turning on itself – people are getting as naked as possible to bathe now!

LikeLike