‘Green sickness’ was described as a condition ‘peculiar to virgins’, which was said to turn the skin a greenish colour and leave the sufferer weak and melancholic. It was also believed to be common throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, especially in girls approaching puberty and in thin and languid young women. Was it delayed puberty, chlorotic anaemia, or anorexia? We don’t know. Was it, like ‘the vapours’, mostly the result of too tight corseting? Was it a kind of fashionable lassitude, coupled with boredom at the restricted lives allowed to well-brought-up young women? Was it frustrated sexual needs?

The last reported case was in the 1930s. Maybe it was simply an eighteenth- and nineteenth-century term for a complaint we know under another name and now understand much better. Whatever it was, plenty of medical men claimed to be able to diagnose and treat it.

Causes

In the late 17th century, Thomas Sydenham believed it to be a ‘hysterical’ disease affecting not just adolescent girls, but also ‘slender and weakly women that seem consumptive.’ He must have thought it a kind of anaemia, since he advocated swallowing small amounts of iron as a treatment:

To the worn out or languid blood it gives a spur or fillip whereby the animal spirits which lay prostrate and sunken under their own weight are raised and excited.

Casanova, not without a good measure of self-interest, attributed it to ‘excessive’ female masturbation:

I do not know, but we have some physicians who say that chlorosis in girls is the result of that pleasure onanism indulged in to excess.

Daniel Turner, 1714, claimed to have found it in a girl who had been eating coal and described its causes as:

… an ill Habit of Body, arising either from Obstructions, particularly of the menstrual Purgation, or from a Congestion of crude Humours in the Viscera, vitiating the Ferments of the Bowels, especially those of Concoction, and placing therein a depraved Appetite of Things directly preternatural, as Chalk, Cinders, Earth, Sand, &c.

One of the commonest claims for a cause was lovesickness or a similar kind of emotional melancholy. It was believed that those denied expression of their love, such as young girls, would naturally be most at risk. This provided a convenient explanation of, and reason to ignore, awkward moods and behavioural changes associated with puberty. The problem was temporary and would pass in good time, since marriage would prove a complete cure.

Cures

Hannah Woolley, in 1675, took a robust approach:

How to cure the Green-Sickness.

Laziness and love are the usual causes of these obstructions[1] in young women; and that which increaseth and continueth this distemper, is their eating Oat-meal, chalk, nay some have not forbore Cinders, Lime, and I know not what trash. If you would prevent this slothful disease, be sure you let not those under your command to want imployment, that will hinder the growth of this distemper, and cure a worser Malady of a love-sick breast, for business will not give them time to think of such idle matters.

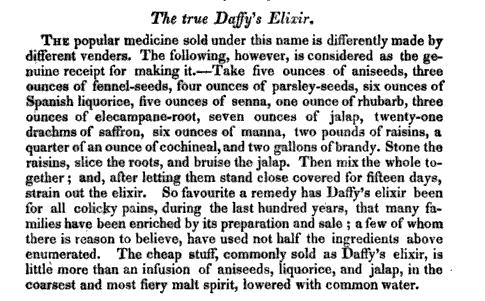

John Hooper’s Female Pills were sold in the 1700s for ‘green sickness’ and were guaranteed to contain “the best purging and anti-hysterik ingredients.” They were best taken with tepid baths and plenty of exercise. Daffy’s Elixir was another strong laxative and purgative cure-all. “Active friction with a flesh-brush” for fifteen minutes over the stomach and bowels was yet another recommended remedy.

Iron could be taken in the form of pills made from sulphate of iron, ipecac, ‘aromatic powder’ and extract of gentian, or by taking the waters at an iron-rich spa, like Tunbridge Wells.

The fastest ‘cure’ of all was said to be sex, since semen was believed to ‘settle’ the womb and allow the humours to evacuate. Do you think a man thought that one up? As long ago as 1554, the German physician Johannes Lange described the condition as ‘peculiar to virgins’ and recommended turning to frequent copulation as a cure, especially when it led to pregnancy.

Here are some of the words of a bawdy song of the time:

A Handsome buxom lass lay panting on her bed,

She looked as green as grass, and mournfully she said:

Except I have some lusty lad to ease me of my pain,

I cannot live, I sigh and grieve,

My life I now disdain.But if some bonny lad would be so kind to me

Before I am quite mad, to end my misery,

And cool these burning flames of fire

Which rage in this my breast,

Then I should be from torments free

and be forever blest.

A sturdy lad overhears this and hurries, at great personal cost, to give her swift relief! So pleasant does the treatment prove that, though she is now fully cured, the young lady resolves to continue taking it on a regular basis.

What was it?

Was ‘green sickness’ physical or psycho-somatic? We don’t know. Was it one condition or several? Again, we don’t know. Something produced these symptoms in enough young women for doctors of the time to see it as a common ailment. It may have been anaemia, it may have been anorexia, it may have been some genuine problems with starting menstruation. It may just have been the vague melancholy, moodiness and lethargy associated with a period of significant hormonal changes. Perhaps it was all of these, different combinations in different people, run together into a single diagnosis.

Whatever it was, it served as a handy catch-all term for the belief of the time that women who did not — or would not — function fully as women were headed for health problems now and in the future. Choosing long-term virginity, a state associated with nuns, was viewed with great suspicion in Protestant England. Women were expected to marry and spinsters were more despised than pitied, even if they were useful as unpaid servants for their married sisters and nursemaids to elderly parents. Just as in men, denial of one’s sexual instincts was deemed unnatural. Men, of course, could mostly indulge where and when they wished, while women were expected to be faithful and chaste.

Well, that was the theory. The reality was often quite different. Compared with the buttoned-up Victorians, our Georgian ancestors were nearer to the attitudes of the 1960s than the 1860s.

- The reference to ‘obstructions’ is based on a common belief of the time that, until a girl stated menstruating, the ‘humours’ built up in the womb and festered. ↩

William Savage writes historical fiction set in eighteenth-century Norfolk in the years between 1760 and 1800. This was a period of turmoil — constant wars, the revolutions in America and France and finally the titanic, 22-year struggle with Napoleon. The series featuring Dr Adam Bascom, a young gentleman-physician caught up in the beginning of the Napoleonic wars, takes place in a variety of locations near to the North Norfolk coast. The Ashmole Foxe series is located in Norwich. Mr Foxe is something of a dandy, a bookseller and, unknown to most around him, quickly involved in dealing with anything likely to upset the peace or economic security of his beloved city. You can check out both series here.