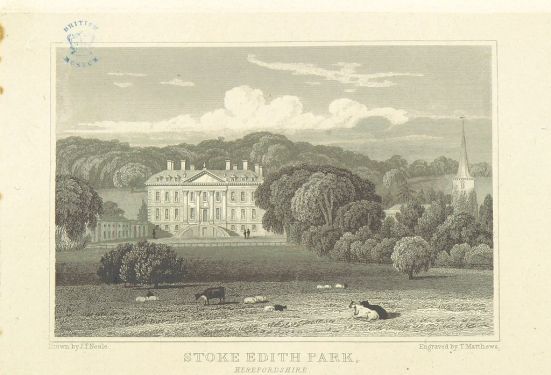

Stoke Park

Note the thick shrubbery in front of the church!

Our Georgian ancestors were just as interested in celebrity gossip as anyone today. The greatest celebrities of the time were to be found amongst the aristocracy; one of the finest sources of gossip came from court cases concerning ‘Criminal Conversation’ (Crim. Con.): civil cases in which an aggrieved husband sued for compensation from his wife’s lover for loss of ‘conjugal comfort, society, and assistance’. Since the essence of these cases was to prove the dealings between the plaintiff’s wife and the defendant were adulterous, the courts were treated to a mass of detailed evidence to prove the two had been up to no good. A successful case might be the prelude to a divorce, although divorces were both expensive to pursue and difficult to obtain. Many a husband remained content with the public shaming of the two parties that a Crim. Con. case produced.

Newspaper reports of the cases tended to be fairly circumspect in their language, but many pamphlets were produced in which the more salacious details were set out in full — or hidden only by dashes and asterisks. Such was the taste of the public for this kind of document that one London publisher produced a book in 1786, entitled “Trials for Adultery: Or, the History of Divorces”, which ran to seven volumes!

In this post, I’m going to concentrate on just two cases. These are the two which, combined with new trends in landscape architecture, turned the word ‘shrubbery’ into one of the favourite printed euphemisms for locations for aristocratic sexual naughtiness.

The Fashion for Shrubberies

Thanks to Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and Humphrey Repton, the fashioning of parks and gardens surrounding aristocratic mansions had changed markedly. Rather than the formal, geometric arrangements found on the continent, British landscape architects favoured a more natural style of pleasing walks and vistas to produce a harmonious blend of open spaces, trees and coverts, which would lead the eye through the landscape towards a suitable feature, such as a folly, often in the shape of a classical temple, or a distant body of water. The shrubbery was an essential element in this process, especially in the work Humphrey Repton. It provided shelter from the sun and wind, a pleasant area in which to walk or a secluded place to read, picnic or — naturally — to indulge in activities you wished to keep away from prying eyes.

Lady Foley and Mrs Arabin

Motion for a new trial on behalf of Lord Peterborough, in the action brought against him Mr. Foley for crim. con. with Lady Ann Foley, came on to be argued. The ground on which Lord Peterborough contended for a new trial was, that the verdict which was for plaintiff, Mr. Foley, with 2,500l [£2,500, maybe be £450–500,000 today] damages, was against evidence. At the trial it had been attempted to be proved, that Mr. Foley was privy to, and conniving at the general incontinency at least of Lady Ann, if not conscious of the present instance of infidelity ; and that he did not use all those means which he ought, to have prevented it. Mr. Mingay argued, that a husband, in such a case, should not be suffered to take advantage of an injury which he might have prevented and compared it to the case of Sir Richard Worsley, in which Lord Mansfield laid down the rule of law so to be. —This rule of law was not denied Mr. Foley’s counsel; but it was strongly contended by them, that there was no evidence whatever of any such fact; and of this opinion was the Court unanimously . . . The rule for a new trial was therefore discharged, and Mr. Foley remains in possession of the verdict.

(Hereford Journal, Thursday 05 May 1785)

The successful case brought against the Earl of Peterborough at Hereford Assizes by Edward Foley hinged almost entirely on evidence from a passerby on what he had seen taking place within a shrubbery on the Foley estate at Stoke Park, Stoke Edith, a few miles from Hereford. So intrigued did the public become with this particular case of aristocratic naughtiness in the shrubbery that the trial was written up in great detail in a publication entitled “The Trial, with the Whole of the Evidence, and the Speeches of the Counsel, &c. In an action at…Hereford…wherein the Hon. Edward Foley was Plaintiff, and the Right Hon. Charles Henry, Earl of Peterborough and Monmouth, Defendant, for Criminal Conversation with Lady Ann Foley… For Adultery”(G. Lister, London, 1786).

The Arabin case took place in 1785 and also centred on evidence involving Mrs Henrietta Arabin’s frolics with a Mr. S—n in a shrubbery in their villa garden. Links to the Foley case became explicit as in this comment:

It is pretty remarkable that Mrs A—b—n’s shrubbery frolic, should have been the exact counterpart of that of Lady Ann Foley. —From the above examples, the nurserymen have been applied to for the purpose of planting with thick growing shrubs several fashionable villas!

(Morning Post, 28 June 1785)

In yet another successful publication on this topic, comes the following statement:

“Fidelity in Wives is all a Joke,

Whilst there is a Coffin,

Shrubbery, or Oak.”(“Amusements in High Life, or Conjugal Infidelities in 1786”, G. Lister, London, 1786).

I’m not sure about the coffin. That sounds rather uncomfortable to me! Yet another publication included this snide comment, with its reference to both villas (the site of Mrs Arabin’s amours) and estates (alluding to Lady Foley):

A correspondent who has been present lately that the sale of some villas and estates, observes, that the auctioneers dwell much on the excellence of the shrubberies, in their encomiums; and that this circumstance generally weighs more than all the other good properties of the estate. The style is generally thus — dining room, parlour, four-post bedstead shrubberies, &c. &c.

(Morning Post, 7 July 1785)

Shrubberies were planted in many of the pleasure gardens in London and provincial cities; places notorious for the liaisons that took place in their remoter regions. This may have added to the idea linking shrubberies and sex in the public mind. I don’t have to explain the various other salacious comments in which male trees and female shrubberies were linked.

Adulterous goings-on could take place almost anywhere suitably private and tolerably comfortable, but somehow the shrubbery seems to have become indelibly associated in the public mind with an aristocratic contempt for morality and respectability. As a result, it featured heavily in jokes, double entendres and euphemisms. Since the discovery of the guilty couple also usually involved a Peeping Tom, spy or curious passerby, this linked the supposedly hidden misbehaviour of the aristocracy to ordinary people going about their day-to-day life.

What more could a newspaperman ask for?

Ooo-la-la! Those Georgians knew how to have fun in nature! So nice to see that human behavior hasn’t changed!

LikeLike

It gives an interesting extra meaning to “Come into the garden, Maud”, doesn’t it?

LikeLike