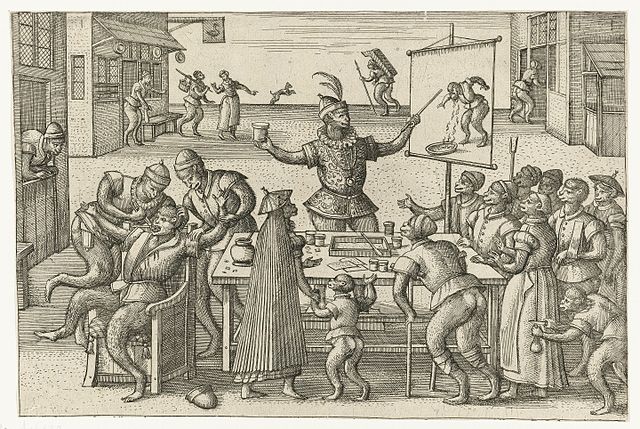

The Quack Doctor: Pieter van der Borcht

One of the hardest mental exercises for any writer of historical novels is to forget much of what you know about how this world of ours works. It’s true that the Georgian period marked the very beginning of a scientific approach to understanding, based on experimentation, measurement and collecting of evidence. However, such ideas were still restricted to the educated elite. For the vast majority of ordinary people, little had changed since mediaeval times. Medicine was stuck in the study of Galen and the belief that disease was due to an imbalance of humours. Germs and infection had yet to be linked. If the primitive, largely useless medical tools of the day failed, you either got well on your own, lived maimed and crippled, or died. Too often, it was the last.

Faced with so many terrors and misfortunes, people sought an explanation of their causes, which might offer ways to lessen or avoid them. “Why me?” is the universal cry of those in distress. “What do I do now?” is equally common. Even for the faithful, being told it’s God’s will brings little comfort.

Ordinary people in Georgian times turned to three sources to answer questions about the misfortunes they encountered. One was religion. “Why me?” and “What now?” could also be answered via two different kinds of understanding: magical practices and other supernatural sources, such as curses, charms and superstitions.

The Power of Tradition and Folk-Memory

What we now dismiss as quaint superstitions — if we recall them at all — were matters of vital importance in Georgian times, especially in the countryside. To ignore or overlook the proper rituals and actions associated with key events in the agricultural year was to invite disaster. Even if you had no firm explanation for such beliefs, save that things had always been done that way, to ignore tradition was to behave with arrogance towards the natural world and the spirits which lurked there. Such pride would bring punishment. Folk tales abound in stories of careless or arrogant humans suffering bad luck — or worse — as a result of not doing things as they should be done. That, of course, meant doing them as they had always been done.

A range of rituals were used to secure good fortune and a bountiful harvest. We still can’t control the weather, but we do know pretty well what to do to ensure sufficient fertility for the crops; and how to destroy pests that might ruin the harvest. Such scientific ideas about crop yield were in their infancy in the 18th century. Destroying pests was based on good husbandry and hard labour. More modern ideas in both areas had reached only the wealthiest landowners and their agents. The ordinary farmer or farm-worker either hoped things would turn out well, or turned to age-old traditions that promised answers used many times before.

Folk Medicine

Much the same applied in cases of sickness. Professionals, like physicians, apothecaries and surgeons charged fees beyond the ability of the poor to pay. Folk remedies, written in household manuals and cookery books, cost nothing. Many were memorised or written out for use when needed. Even the mistresses of grand houses did the same, especially with herbal remedies. After all, they did as much good as the bleedings and cuppings of the physicians, or the opium and cocaine based medicines sold by the apothecaries.

Where literacy was limited, much of this traditional knowledge was kept by the Cunning Folk on behalf of the local community. The Cunning Man or Woman would have learned their lore from their parents or grandparents. Knowledge was handed down orally. Those who possessed it guarded it jealously. It was the source of their income and standing in the community. They spread the idea that to write it down might lessen its potency. They also claimed that esoteric knowledge in the hands of ‘ordinary’ persons was dangerous. In this, of course, they were no different to the medical professionals.

How to Survive

To understand the world of the ordinary Georgians, we must set aside our preconceptions and imagine a society in which health, wealth and life itself were all at the mercy of unknown and inexplicable forces; in which the best you could do was turn to those who claimed to possess the means to tilt the odds in your favour. Quacks were everywhere. Just as today, those who were most plausible were not always the most reputable. To the common folk of the eighteenth century, lacking in education and the time to devote to anything other than life’s basics, the quacks offered quick and easy solutions. The ‘scientific’ professionals moved in lofty circles and spoke using terminology few outside those circles understood. Is it any wonder it took many decades for scientific methodologies to become the norm?

Even today, a surprising number of people still prefer to rely on ‘the wisdom of the ages’, expressed as spiritual or religious beliefs, over rational or scientific knowledge. Billions are made via the sales of ‘Alternative Medicine’, much of which has never been rigorously tested. The only difference is that today’s ‘folk’ ideas are dressed in the expensive designer clothes provided by marketing professionals.

I am catching up on your posts, William, and haven’t been able to comment on the older ones, However, they are always fascinating and I learn a lot. The one on poachers and landowners was enlightening since I only knew one side of that story – probably from reading Robin Hood! I am in the middle of trying to work some medicine into my novel now – found out that women who could write had ‘receipt books’ with the receipts for various herbal remedies. Had fun working in a description of the use of enemas (seemed to be a favorite treatment for many things) for the flux.

It seems medicine had a long way to go even a century later!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I have a transcription of one such ‘receipt book’, dating from around 1710, and it makes fascinating, if sometimes nauseating, reading!

LikeLike